lecture hall

Before the lunch talk on the political economy of the War on Terror, which is mostly about the US using IMF lending to induce Pakistan to support US military initiatives, I talk to D— and Z—, who have never met before. Where do you come from? Z— asks D—, and D— says she feels like she was born in this town and will die in this town. It’s a strange thing to say but I know exactly what she means, about the suffocating totality of this place, how you come here and a set of petty squabbles, incestuous love affairs, and third-rate soirees uninteresting to anyone outside of campus (unless rejiggered into watchable plots, à la The Chair) occupy the whole of your scrambling brain. (Was there anything before? Will there be anything after?)

My housemate who works on primates tells me low-status monkeys are hyper-observant. When they enter a room they consider everyone and everything. They have to exercise vigilance, be on guard in case of attack.

Is it normal for PhD students to know so many people, says D— after I introduce her to Z—, maybe because I’ve nodded at a few others in the room too.

I recognize people sometimes who don’t remember me. A guy I met at grad school orientation. I saw him a few months later, asked if his parents liked their new house. He’d told me they were moving into it when we’d first met. He looked at me in blank astonishment. Where did we meet? he said.

Do I know a lot of people (what is a lot? when does it feel like enough?) because I like to, or because I’m nervous, or is it a little bit of both?

seminar room

Every Tuesday morning I have a history class on liberalism.

The student who sits directly across from me speaks glowingly of eugenics and says attempts to rehabilitate Nietzsche and save his legacy from fascism are wrongheaded, that instead one should acknowledge the “kernel of truth and goodness” at the heart of Italian fascism and Nazism. Which is? asks the professor. The higher breeding of humans, says this student.

In this same class we read Richard Rorty on liberalism and irony. In his book, Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, he introduces the figure of the liberal ironist — “someone who understands that any particular description of reality or of the self that she might adopt will be adopted only for contingent reasons, often having to do with her culture and upbringing” per SEP’s entry, able to reconcile that contingency of values with retaining ethical commitments, like not being cruel to people.

I think about the position of the ironist, the smug superiority of being an ironist among naïfs, the way it describes some cold, smart people who frighten me. The pro-eugenics student conveys affective commitment to what he says, though I also wonder how much it’s possible to a) say things you know are noxious to everyone around you and b) not acknowledge this, and not be some kind of troll.

Another student deftly turns from Nietzsche back to Rorty. There is no anger expressed by anyone at the pro-eugenics student. I’ve gotten into arguments with him too many classes in a row and I’m not sure what the point is. Here I don’t want to cede any ground, imply that what he’s saying is worth debating, but I also worry sidestepping it completely indicates moral laxity. There’s a rotten smell in the air and we’re all talking blithely about the weather. Is everyone else an ironist, or pretending to be?

living room

Becca Rothfeld writes in her recent Substack about writing as a space to figure things out. This is how I use talking about things too. I felt badly hurt a few nights ago, sitting on the couch in my apartment’s living room. I was trying to collaborate with someone, to write an essay together. I asked him to tell me about his ideas and I typed them up, as faithfully as I could, which is pretty faithful because I type quickly. Enough bullet points to fill a page. I had some concerns about the originality, the reading of the text in question, but set these to the side. The first task, especially at this stage, I felt, should be ideation, and we should be fruitful, multiparous.

So I nodded and asked a clarifying question or two but otherwise tried to stay as neutrally supportive as a therapist. When I shared my idea, he did not type, and quickly began asking questions in an adversarial tenor. What’s different about this from ____? You’re saying the book is only optimistic because of the emails? Yeah, I don’t buy it, and these 5 words were so acerbic: Yeah, I don’t buy it. Clipped and dismissive and final.

Look, I said, I listened carefully while you talked about your idea and wrote things down and you’ve just been sitting there telling me why I’m wrong.

My apartment is a homey place, largely through the efforts of my other housemates, who placed a giant painting on the mantelpiece and seasonal decor on the coffee tables. The conventions of the academy, the skeptical questioning, felt like an incursion here. There’s no reason this space should be set apart from the seminar room or the public square, I guess. The training of this semester sends the thought into my head: isn’t the whole division of public and private itself this abdication of the liberal state of responsibility for all the wrongdoing in “private” life, see Carole Pateman, and yet I don’t want to be sitting there on the couch with this collaboration disintegrating, circling the drain.

Maybe it’s more than a resentment about school entering home. It’s also this: why should school so often feel like not-home, a place of guardedness and vigilance? I want the seminar to feel kind, nice, smell like roses and hot cookies. To be joyful, to be ludic. So much of the emotional awfulness day to day comes from the assumption that fighting is generative, that we can access some deeper truths through trial by combat. Maggie Nelson has this line in On Freedom: “many men are comfortable in role of guru because it places them in the position of purporting to know […] [they turn to] performance of mastery as well as, or in place of, care provision.”

living room

The room where I went today to talk about my research in progress was another living room, but sort of a false one. It belonged to a college head of house, a sociology professor, and I was so tired, tired of trying to demonstrate mastery. Sometimes in these rooms where people come and go eating sandwiches, I think, Why aren’t we all screaming?

People give their good comments, smart comments. Weekends ago two friends from college were visiting and one said, hearing about my research, That sounds emotionally taxing, how do you deal with that? and I was sort of overcome with gratitude in this moment, because it was a question that came from care.

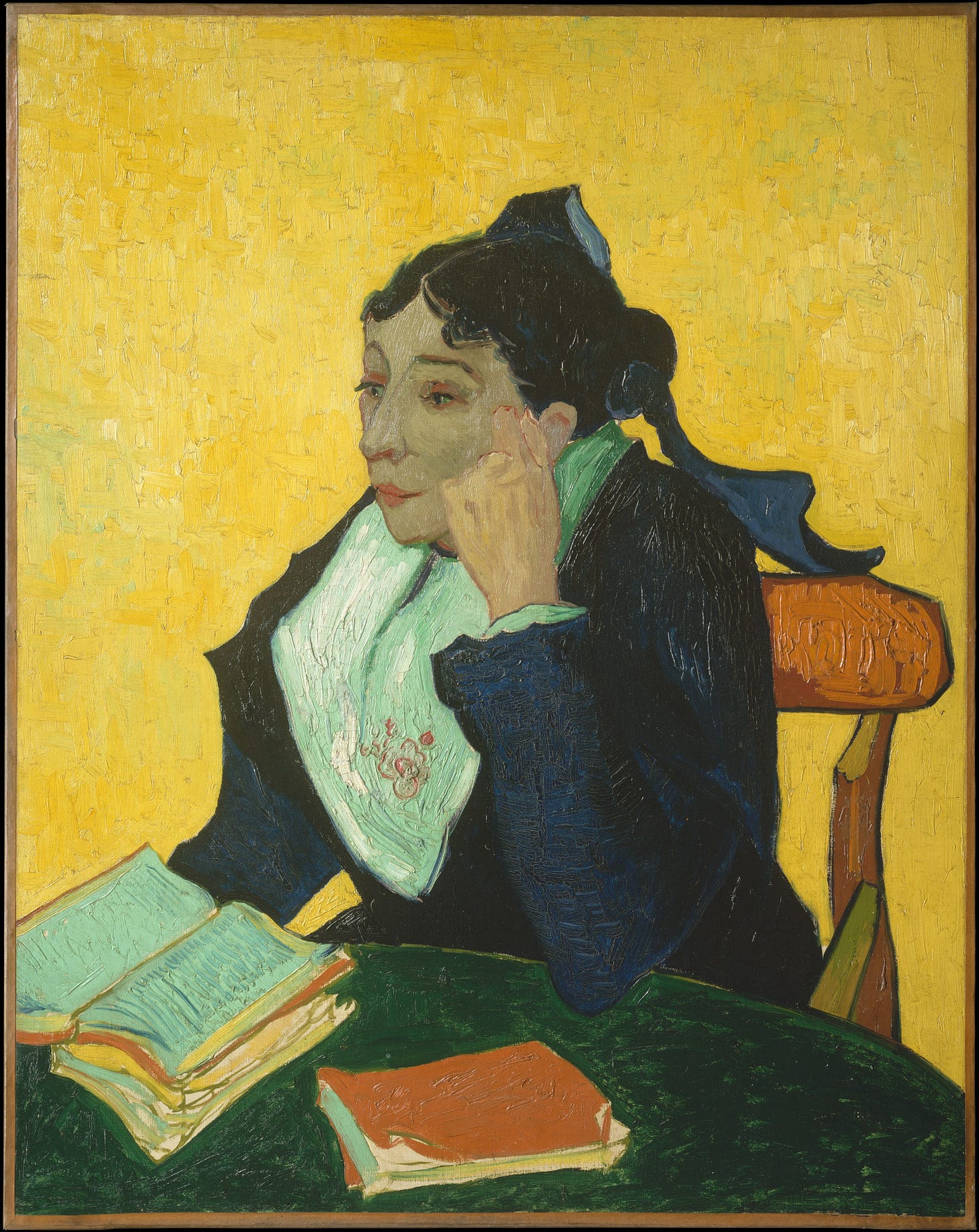

image: Vincent Van Gogh, L'Arlésienne: Madame Joseph-Michel Ginoux (Marie Julien, 1848–1911). The Met Collection.

been reading —

a Rorty essay about growing up in a leftist social milieu, “Trotsky and the wild orchids”

This poem, in Eileen Myles’ anthology Pathetic Literature: