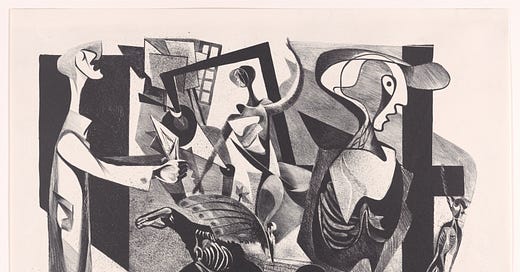

journey to the west

Vision. Joseph Vogel. Public Domain.

Do you remember this Save the Children video from 2014, “Most Shocking Second a Day”? Made by the London-based ad agency Don’t Panic, the 93-second video features a young British girl’s life in the “one second every day” format: we see her blowing out the candles on her birthday, walking to school, and seeing family and friends. But all is not well: the dissolution of her happy world is foreshadowed in ominous news stories on the TV in the background (“violent clashes with…”), then conversations (“...deserve to get shot”) that turn into power outages, airstrikes, burned-out apartment blocks, and ultimately her escape to a refugee camp. At the end her youthful face is ash-covered, sober, haunted.

“JUST BECAUSE IT ISN’T HAPPENING HERE,” reads the text on the final shot, “DOESN’T MEAN IT ISN’T HAPPENING.”

Save the Children launched the campaign to bring attention to the Syrian refugee crisis. With Don’t Panic, they made a canny bet: that it’s easier to trigger the empathy of Western donors with imagery of a white child in a Global North metropolis suddenly ravaged by war than any other child in any other place. I too watched the video, felt the knife turn at 0:20 or 0:27 or 0:36, the descent into horror. Later, when I worked in a nonprofit communications job that entailed occasional collaborations with ad agencies, I thought of this video again. After all, “Most Shocking Second a Day” was a success story: it received over 74 million views.

As Ukraine’s ordinary men and women as well as mayors and MPs take up Kalashnikovs to defend their homeland from the Russian invasion, global coverage has reiterated shock and astonishment. You can find the lowlights on any number of Twitter threads — consider CBS foreign correspondent John D’Agata saying “This isn’t Iraq or Afghanistan…this is a relatively civilized, relatively European city,” or an Al-Jazeera English anchor saying “These are prosperous, middle-class people...not obviously refugees trying to get away from areas in the Middle East... in North Africa." Everywhere is incredulity at the fact that now, it is happening here. But where’s “here?”

The “free world,” says Biden in the State of the Union. The West, if you listen to headlines. “Putin’s Endgame: Russia vs. the West.” “The West finally throws a punch in its face-off with Russia.” “How Zelensky changed the West’s response to Russia.”

The West is a fantasy, a fever dream, a collective delusion. “I know it when I see it,” not a well-demarcated line that you can point to on a map. The West — inheritor of that old division, the Occident and the Orient, maybe less freighted by pith hats and the scent of patchouli.

Lisa Lowe writes in The Intimacies of Four Continents that the preconditions for the development of European liberalism lay in the colonial subjugation of people across Africa, Asia, and the Americas. The political philosophers could only conceptualize “the human” with all his darling attendant rights (life, liberty, property) because of the less than human, vast swathes of the world’s people consigned to this subordinate position by the logic of racial difference and development hierarchy. John Stuart Mill argued for colonial despotism in India by saying the Indians were simply not ready for self-government. Where would Britain be without her economic gains from the brightest jewel in the crown? Put differently, there is no free world without the unfree world the colonizers forged.

It’s this fact that makes the immigration and asylum policies of numerous countries so reprehensible. Numerous European countries have turned away refugees from Afghanistan, Iraq, and Syria; they’ve invested in militarized borders, shoring up the walls of Fortress Europe. But something different is happening now. Bulgarian Prime Minister Kiril Petkov stated, of entering Ukrainian refugees, “These are not the refugees we are used to… these people are Europeans. These people are intelligent, they are educated people.”

Paul Farmer, the doctor and founder of global nonprofit Partners in Health, died recently. He famously advocated for some of the poorest people in the world to access gold-standard healthcare, even taking expensive antiretroviral medications door-to-door to patients in Haiti. He said, “The idea that some lives matter less is the root of all that is wrong with the world.”

Why do some lives matter less? Is it just about being part of the West?

Back in 2016, the writer Sophia Benoit posted pictures of pre-bombing Aleppo on Twitter:

The pictures she chose, in order, depict: people walking along a shopping street, an orderly avenue, the lit-up city skyline at night, and taxis and shuttle buses outside a Sheraton hotel. The second photo, with its cars sparsely dotting a road, a perfect line of trees in the median, feels almost empty of life — there’s one man at the crosswalk. Its message is structure, not vibrancy. There’s an argument being made for empathy with this set of pictures, but what is it premised on? Is it the people? The stability, the sedateness, the spatial logic? The unbrokenness? The Sheraton?

To be clear, I like her tweet. I like resisting the “monolithically war-torn” narrative. But I also wonder what it does when we stake claims for compassion on the order of things, electric grids and high-rise apartments, assimilation into global markets. The accoutrements of modernity and a beautiful past.

The last international trip I took before the pandemic was to a place now well assimilated into global markets: Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. I joined a free walking tour of the city that met a couple hours before sunset. Our guide pointed out bullet holes in buildings from World War II, and later, a state building damaged by NATO bombing in the 90s. After gesturing to these still-standing monuments to the ravages of conflict, he handed out small plastic cups of his grandfather’s homemade fruit brandy. He had some more bottles in his bag, he added, if we’d like to take any home. Our little international group strode on the walls of a citadel under a darkening sky. Later, hungry and cold as the night chill settled, I wandered into the Rajićeva Shopping Center and ate at Vapiano, an Italian fast-casual franchise headquartered in Germany. In a world made safe for capital, everywhere is somewhere you’ve been before.

The next day I visited the Temple of St. Sava, a beautiful Serbian Orthodox church with a dome modeled after the Hagia Sophia’s. I noticed on one of the signs outside the church that Gazprom was a major sponsor of its renovation. Vladimir Putin himself laid a stone in a mosaic when he visited in 2019. The Russian state likes to flex its muscle this way. In Syria, they’re investing in the restoration of the ancient town of Palmyra. There’s something especially perverse about this, in a country where children died in the firestorms Russian planes delivered. A professor I had in college said that the logic of war is the desire for land and not people, that the people are dispensable. I think that it’s not just land but artifacts, churches, relics with dust in their mouths, the statues who can’t speak. Sometimes the right buildings and gleaming things inside glass cases tip the scales enough that we decide someone’s life matters. Or they shop at a LVMH subsidiary or drive a Tesla out of their burning city and we decide their life matters. Or they have blue eyes and we decide their life matters. I don’t know.

At the shrine A. says to send compassion radiating outwards and I squeeze my eyes shut, think of the people I love, then a bigger circle, huddled families in the subway stations turned bomb shelters, finally all living beings. Does it get weaker like a radio signal I wonder, does it do anything at all.

March doldrums / shifting in my seat / this waiting room for Spring. / how i love the glass world when the snow melts& freezes over / by 9 it is all quiet on my street / settles over my ears the blue sound of cold.

solid advice: How to support a friend going through a difficult time